Casey Ellis grew up just a few houses away from the Owen County Hospital in Owenton, Kentucky, so he knows the essential role a rural hospital plays in a small town. Ellis is Judge Executive of Owen County, a job his grandfather and great-grandfather had before him. So he also knows how hard it is for a rural community to keep a hospital.

“I have always seen it struggle,” Ellis said. “I grew up seeing it struggle.”

Over the years, he’s seen it operate as a for-profit hospital, a non-profit, and under a private owner. The community even established a foundation to support it.

“I mean, the writing was on the wall,” he said. “They were just losing too much money.”

After the hospital closed in 2016 its emergency room continued operation under new management. That only lasted about 18 months.

The closing of the Owen County hospital is part of a growing trend across the Ohio Valley and across the nation.

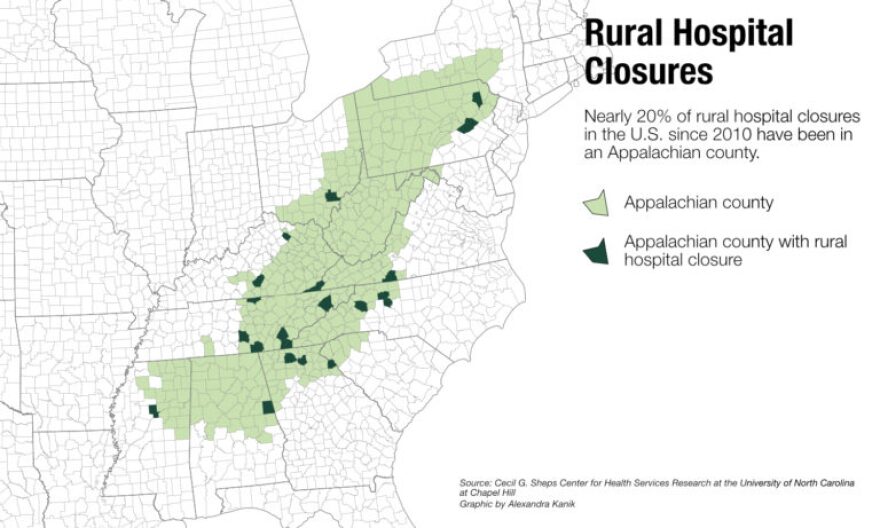

So far 106 rural hospitals have closed since 2010, according to the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and research shows the trend is accelerating.

In the Ohio Valley, Belmont Hospital in Bellaire, Ohio, closed last month after a century of service. Officials in Pineville, Kentucky, are scrambling for options to save their hospital, even holding community prayer services.

But troubles are of the earthly kind. Populations are declining and buildings are aging. But the biggest challenge, according to experts, is that the money going to pay for care is more than the money coming back in reimbursements.

That leaves communities like Owen County struggling to find other ways to provide care.

“There’s only so much you can do, there’s only so much in tax dollars, because we’re not generating revenue here,” said Dan Brenyo, the county’s emergency services administrator.

“If you keep robbing Peter to pay Paul, you eventually are not going to have any Peter left.”

Owen County’s courthouse, where officials are adapting to life without a hospital.

Owen County’s courthouse, where officials are adapting to life without a hospital.

Credit Mary Meehan/Ohio Valley ReSource

Tough Economics

Hospitals have a symbolic significance to rural communities; they are where babies are born and loved ones draw their last breath.

Hospitals also make important contributions to the economy. In some cases, they are the community’s largest employer.

But it is getting more and more difficult to make the finances work in small rural communities.

Ty Borders is the director of the Rural and Underserved Health Research Center at the University of Kentucky. He said access to health care is especially difficult for people in Appalachia.

“The reality is that many rural communities can’t really support a full-fledged hospital. They may need primary care and perhaps emergency department services, let’s say a primary care clinic attached to an emergency department.”

But federal policy complicates that simplified model for care.

“Medicare won’t pay for that,” Borders said. “Medicare will only pay for hospital or emergency department services that are in a hospital. And in most rural communities, that’s a critical access hospital.”

And those are the hospitals that are closing.

As the rural populations continue to decline, Borders said, communities often don’t have enough people to support a local hospital.

To further compound the situation, many rural hospitals were built in the 1940s or ’50s or earlier. They weren’t built to handle modern medical technology and, often, there hasn’t been enough money to renovate or even keep up with critical maintenance.

Belmont Community Hospital in Bellaire, Ohio, is an example of those trends. It served the eastern Ohio community for 105 years before closing this spring. According to the U.S. Census, Bellaire’s population peaked in 1920 at about 15,200. The community currently has about 4,000 residents.

Borders said rural hospitals rarely close abruptly. Often they struggle for years to stay open.

That was true in Bellaire. In 1996, the hospital was purchased by the Wheeling Hospital nearby in West Virginia. Several efforts to save the hospital since then have failed.

When the closing was announced, hospital officials in Wheeling said some of the 93 hospital employees would be offered jobs there. But in another blow to the community, Wheeling Hospital’s former CEO Ronald Violi has beencharged by federal prosecutors with fraud and accepting kickbacks.

Cost of Care

“Most local communities are in a very difficult situation when these rural hospitals close,” Ayla Ellison said. She is managing editor of Becker’s Hospital Review, which covers the hospital business.

Research indicates people are still getting the most critical care. For example, a 2015 Health Affairs study found hospital closures had no effect on mortality for Medicare patients. “Access to care, acute care services are still offered within, you know, relatively close proximity,” she said.

However, Ellison points out, care can become more costly as the caregivers become more distant.

“It affects us all, regardless of whether you live in a rural area or not,” Ellison said. If there is an emergency and someone needs to be transported 50 miles to the hospital, or airlifted by helicopter, that kind of care is expensive. “Everything ties back into insurance rates and the economy as a whole,” she said.

Care After Closures

In Owen County, Ellis said the economic effects have been far-reaching. He thinks about 50 people lost their jobs when the hospital closed. And the lack of a hospital makes it more difficult to draw new employers to the area as the county seeks to replace an industrial plant that closed four years ago, draining another 600 jobs.

Ellis said now that Owenton has no hospital, he’s noticed a change in a traditional practice of some older rural folks. Once, they would tend to move into town as they got older, in order to be closer to medical care. Now, Ellis said, they are moving farther away from town toward quicker access to a hospital in other nearby communities.

Ellis said county officials have done what they can to stretch their health care dollars and serve the about 11,000 people across roughly 350 square miles.

o help make sure people can get to care quickly, officials developed 18 helicopter landing sites since the hospital closed. And to make sure people are using care wisely they have engaged in education and outreach.

“We did a huge campaign on when to call 911 because we didn’t have a hospital here, we knew we were going to have extended transport times,” he said. “We wanted folks to have a real understanding of what was appropriate and what was not appropriate.”

Brenyo, the emergency services administrator, said ideally the county would operate a home health program in tandem with emergency services. But that’s just not possible with limited personnel.

“A lot of rural counties just can’t do it, because we just don’t have the folks to do it.”

He worries about assigning limited emergency responders to other tasks. “We can’t send a paramedic 20 minutes down the road to go see Miss Joe to change her bandage talk about her medications,” he said, if that means risking a situation where no one is available in a crisis.

“If he’s the only one in the county and then we’re having a heart attack two blocks down the road.”

Brenyo finds he is competing with other hospitals when recruiting paramedics. In Kentucky, paramedics are allowed to work in a hospital setting, and Brenyo said that can be an attractive offer due to better pay and more stable hours. Fewer paramedics want jobs like the ones in Owen County. Brenyo said he’s short-staffed and the county operates just two ambulances.

Brenyo is acutely aware of the looming threat of a multi-car crash or some other mass casualty event.

“We will do what every other rural county does in America,” he said. “And that’s ask for assistance from other towns and communities, and just hope that they have available units that can come.”

Correction: This story was changed on June 17, 2019, to correct the spelling of Judge Executive Ellis’ first name. It is Casey, not Carey.